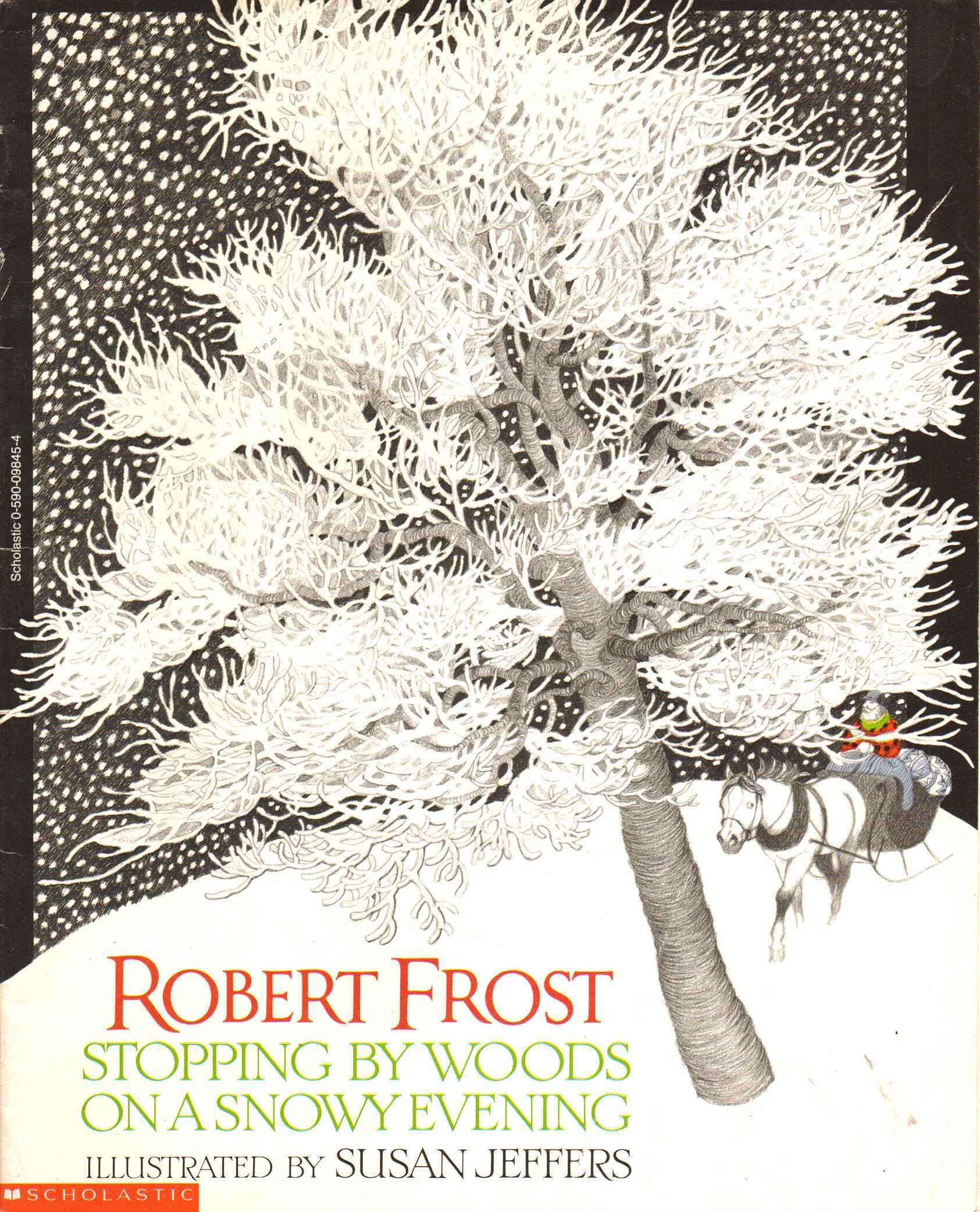

We have been fond of this children's version by Susan Jeffers, reading it first to our children and now to our granddaughters. We tell them that this is about places nearby, of course, and that my grandfather - their great-great grandfather, had Frost as an English teacher at Pinkerton Academy in 1910. (Gramps wasn't impressed, BTW.) Last night I taught about rhyme scheme as well. I think I'll do alliteration next. The Jeffers version is a bit too cheery for the text. The narrator brings food for the woodland creatures that he leaves behind, and frolics in the snow making snow angels. He looks a bit like Santa. That's fine for them now. I can bring in darker meanings later. What fascinates it that even papered over with such lightness, the poem is somber, even melancholy. There aren't many other ways for "darkest evening of the year" and "miles to go before I sleep" to come across. The last illustrations are near white-out blizzard.

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must thing it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound's the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

There was controversy about a comma in the last stanza, though no longer. A friend we had over last night, who teaches composition put me on to that, and I had fun reading up on it. Frost's first editor inserted a comma after dark, which changed the meaning somewhat. With the comma, the woods are three things - lovely, dark, and deep. Without the comma, the woods are lovely, while the words dark and deep are descriptors why or how they are lovely. They aren't lovely and dark and deep, they are lovely because they are dark and deep. Frost's original way, and the only way used now, embraces the darkness more.

There is a sort of mind that reads a lot of poetry which wants everything to be about death, or even suicide. That is a common interpretation, and the melancholy notes of the poem make that plausible, even though Frost denied it when asked about it. A second interpretation is that the woods represent a dreamland, a place to get away from the many pressures and responsibilities of life, temporarily or even running away and making it permanent. The last stanza makes it clear that whatever the woods are, the narrator is tempted to linger or even enter them. My own thought is that all of these are suggested but none insisted upon, like the melancholy thoughts one has while staring at the embers of a dying fire. The thoughts seem deep, and wise, and include regret and resignation. Yet when we call them up later, what were we thinking about really? It wasn't lost love or lost fortune or lost opportunity, it was a mood, a mood which vaguely included all these things. In such a mood, one can be both haunted and wistful about going into the woods.

This is set up right from the start, with the narrator letting us know this is all a bit odd. Why even think or care about whether anyone would see you stopping by to look at woods? The uncertainty of who the owner even is makes the point of contact between the responsible civilised world and the dreamland, even death-and-disappearance-land, even more of a borderland between the two choices. I will note that much is made in commentaries of the horse not really thinking such thoughts as suggested, but having them projected onto him by the narrator. They don't know horses, then. Horses trained to do a certain job, such as deliver milk in a city or carry owners between towns and houses do indeed have a sense of how things should be, and act a little uncomfortable and impatient when things do not go according to plan. Horses like predictability. The horse is a live creature, and thus a tie to the world of the real and the living.

The poem might almost end on an upbeat note at "promises to keep," the poet having briefly considered leaving the responsible world for an hour or a year but quickly deciding not. He will return to a world where he has people who expect him. The repeated last line with its miles and sleep is more resignation, even wry acceptance than despair, but it prevents any cheerful interpretation.

No comments:

Post a Comment