I took notes at the exhibit at the Morgan Tolkien: Maker ofMiddle-Earth

and expected to comment immediately, while it was fresh in my mind last month. I am glad I held off. Much of the exhibit is about his own maps and

artwork. The editions of Tolkien I have read, right from the beginning, have

had the maps, which I loved, and artwork by others, which I have been lukewarm

about. When I was exposed years later to

Tolkien’s own illustrations I didn’t like them any better, which surprised me.

Smaug seemed more cartoonish than frightening, the original Hobbit dust-jacket put me off with its

blobby trees and impossibly-steep mountains. Those are fine to designate

mountains or forests on a map, but only by convention. I have looked at his

other illustrations over the years and simply shrugged. Not much of an artist. Not sure

what ridiculous school of art he was trained in to be so stylized. I’m glad his

words are so powerful that I don’t have to rely on the drawings.

The exhibit portrayed them in a way I had not thought through: they

are not illustrations of real scenes, but of myths, or even the hazier, the emotiveprimary process

images that myths are founded on. I step backward into one of my own set of

rules, which I had been ignoring for this topic all these years: Goethe’s ThreeQuestions. What is the artist trying to

do? How well did he do it? Was it worth doing? The first two must be answered before the

third is attempted.

Tolkien of course knew these are stylized, not “convincing”

in any realistic sense. He didn’t intend us to have that naturalistic

experience of “feeling we could almost touch” the dragon’s claw, or some

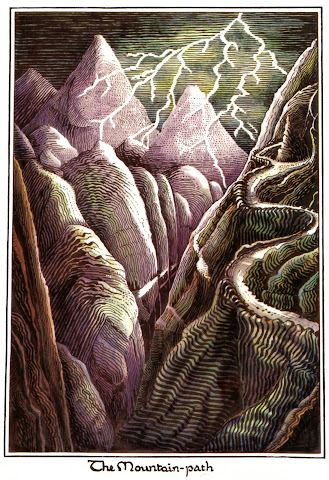

near-photographic reality of a mountain landscape. He wanted install the deep memory of myths in

our minds, of roads going up into distant mountains, or dark, impenetrable woods

as caught out of the corner of our eye. These grow up in a culture over

generations of songs, folktales, rituals and phrases and become the mind’s

landscape, not the photographic landscape.

This would be a good spot to click through to the exhibition website

above and click on the video. The

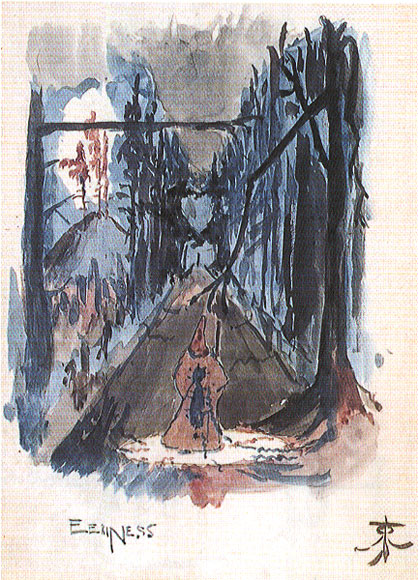

drawing “Eeriness” long predates any writing of The Hobbit yet could well be from

Middle-Earth. The trees have some impossible angularities and convergences. The foreground figure

could be a wizard, and the distant figure in the road, a mere stick, might

portend either danger or rescue. Or nothing at all, simply another tree in the forest.

I recall how distressed I was when I learned that a maker of

horror movies was going to be doing Lord

of the Rings. It offended against the literary Oxonian feeling of gowns and

dons. Still, I thought later, this is the Tolkien who wrote “Beowulf:The Monsters and The Critics.*” The fantasy, gothic, horror, and science fiction

genres were not distinct when he was writing.

JRRT had a great deal to do with making them more distinct. I have never liked the horror genre. But LOTR has a lot of elements of a horror

novel, as does Beowulf. The monsters are central. Peter Jackson turned out to

be the correct choice. The Beowulf poet uses a literary device to create a

greater sense of ancientness. Grendel is

old, and has long troubled mankind. Thus when a second monster is introduced

and it is his parent, we have an immediate sense of greater age and remoteness.

Further description traces her all the way back to Cain, to the foundations of

humankind. The was something similar visually in the beginning of the first

Star Wars movie, when we see the hugeness of the ship chasing the small

fighters. There are long seconds running

under its great length, impressing us with how outsized is this ship compared

to its opponents – yet the camera draws back to show that the unimaginably long

ship is in fact quite modest in size compared to another ship. We are jolted

into seeing the immenseness of the latter.

Tolkien does something similar with the ancientness of his monsters. In

Moria the dwarves seek knowledge of the death of a reestablished colony from

decades before – already dusty, old; they read in a damaged record the colony

was destroyed when it awakened an enemy that had troubled them in early,

brighter days, deep in their history; when the Balrog fights deep in the earth with

Gandalf we he was already impossibly old before that time, long predating the

coming of the dwarves to Moria. The technique is used with Shelob, with the

Ringwraiths, and with Sauron himself. We look back through many glass walls to

see their beginnings.

He uses the same technique to create myth. His hope was to create an English mythos

similar to the Finnish Kalevala. He

does this by having characters tell much of the story retrospectively. We do not follow the attack of the Ents on

Orthanc in real time. Merry and Pippin

describe it for us after. So also with Gandalf’s encounter with Saruman, and his

fight with the Balrog. The device is used right off in The Hobbit, as the dwarves kick off the story by telling a story of ancient wrongs and

ancient treasure. The past is everywhere in Middle-Earth, and there is always

someone to tell you a story about it.

This is economical in the time needed to tell the whole

tale. Summaries of battles, entire wars, or even long ages of history can be

done in a few paragraphs. Imagine how

much longer LOTR would be if all the events were told in linear fashion! Yet I

don’t think efficiency was the primary aim.

Tolkien created an entire history, and used a single great adventure in

it to give us the whole. It is a story

of people telling stories, and even more distantly, repeating legends that have

already changed over time, singing songs of events barely remembered, reading

books that have long been forgotten, in languages and scripts that few read and

none use anymore. Gandalf pores over a text that even its owners have neglected

in Minas Tirith – and unearths Isildur

telling a story. He created layers of history and culture stretching back

into myth, and such things are impressionistic, shadowy, and indistinct,

whether they are grim and eerie, bright and comfortable, or strange

combinations of color and emotion. The tiny stick figure in “Eerieness:” Is

this the long-sought prince, or a final enemy to be fought? Have we seen this before, been here before?

Thus Tolkien’s other art, such as the bright homeliness of

the Shire, or Bilbo’s emergence from shadow into open sun on the barrels at

Laketown, is truer than a photograph. I am sure I have never been there, and

yet, it is like something I remember.

Tolkien is drawing memories of

trees in Faerie, not trees; memories

of landscapes, not landscapes. His characters tell stories, or sometimes only

rumors - not histories.

Additional notes: Tolkien based his stories on the maps and

the languages, and the exhibit has a good deal of his writing on both. While the map changed as Tolkien entered the

world and learned the stories in it, he covering over small sections with new

graph paper as he corrected the landscape, what is remarkable is how little it changed. The first maps are clearly of the same

Middle-Earth, and one could even believe his changes are improvements based on

his visits to the terrain, not adaptations to fit the story. It was also fascinating to see his

side-by-side calendars of the events taking place in different locations after

the Fellowship was sundered, to keep track of all parties as he wrote. There is

a column for Sam and Frodo, a second for Merry and Pippin, a third for Aragorn,

Legolas, and Gimli, with occasional subdivisions when those become divided or

Gandalf’s movements need to be accounted for. According to the book Bandersnatch, there were discrepancies

of weather and phases of the moon in some of the last events when he was

writing quickly, which caused him no end of frustration during rewrites for

publication, as he could not bear to have them be out-of-sync or

papered-over. This paralleling of the

adventures breaks through in the text occasionally as characters wonder what is

happening to the others, or Tolkien inserts a quick sentence to knit us back to

events far away.

I was pleased to learn that JRRT regarded Bombadil as

outside the story, not quite fitting, but necessary not only for plot but

because he is an actual resident of the place.

I had always regarded Tom as not quite part of the story, something of

an insertion. I was not distressed when he was not part of the movie. Yet to

learn that Tom is part of many other stories, though this one only incidentally,

makes entire sense to me. When after long years of avoiding the movie I finally

saw it, I mentioned to my son my comfort with the missing Bombadil. When I had read the books aloud those several

times to the boys I worked very hard to compensate for Bombadil’s distance from

the sense of the story by making him come alive. This drew a flash of anger from my eldest,

that perhaps I shouldn’t have worked so hard at it, then, as he missed Tom very

much.

1 comment:

I want to thank you for this piece, without presuming to comment on it. I just want you to know that I appreciated it.

Post a Comment