Monday, September 23, 2019

Thurber

I read My Life And Hard Times to my two oldest boys years ago, a rollicking good time. I thought it might work for my granddaughters, 8 and 11, as well and I have the opportunity about every other week. (Tracy is reading Charlotte's Web and gets her turn.) The 8 year-old doesn't particularly get it, but the 11-year old likes them and asks for more. This surprises me. As I am reading to a new audience I am aware that these homey, gently humorous stories are now a hundred, not seventy-five years in the past, nor have these girls been as fully steeped in previous eras as their father was. The references are more distant ("What's a rumble seat?") and I have to break for a moment to explain what the GAR or camphor is.

The later stories in the book I left off, after talking with their father. "University Days" would be appreciated only for the incident with the microscope, and "Draft Board Nights" would be nearly meaningless, as it is entirely aimed at an older audience. But it is "A Succession of Servants" that would be the bigger problem, because of the prominence of black characters. It is easy enough to switch in "black" for "colored" on the fly, but the use of hundred-year old black dialect, and the ridiculousness of the characters would be a problem. The black characters are less ridiculous than the white people in the stories by and large, but we bend over backwards not to offend. When they are older they might read the story without harm, and to some profit, noticing the differences between that era and this. We have considered this an important part of reading to them, of opening out other eras to them. The rest of the world will teach them the present, our value-added is in nestling them into other eras. With more recent eras we can do this because we are closer to the time even if it is well before our own birth. More distant eras are things we have read about for years and have more comfort with. We can sense in listeners whose attention is wandering what might need to be said to explain and make it more pertinent to them.

Their puppy ate the back half of the book - entirely appropriate for Thurber and solving my problem - but their over-responsible parents replaced it by buying the entire Thurber Carnival. I thought I would have a new source of short stories, but reading through, almost nothing is appropriate. The other stories focus on the small arguments between husbands and wives, or rather cynical observations about human nature that would be of little interest to the girls. The problem of working around racial stereotypes is even greater in the other stories. They might get the humor of "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty" but I have never much liked it. My son suggests it was the story picked to be anthologised in decades of high-school textbooks because it was shortest.

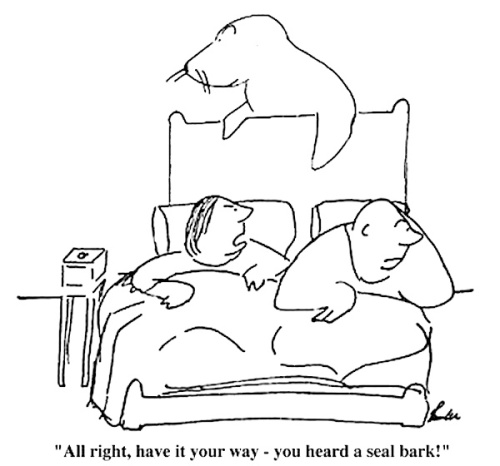

My Life And Hard Times is still accessible to children because it is about his childhood and young adulthood, and so is filled with parents, grandfathers, pets, neighbors, streets and houses, which are familiar territory for children. The world of arguing about restaurants and lighting cigarettes for each other is not theirs. Nor do the cartoons work all that well anymore. The humorous drawings illustrating the story can still be enjoyed, but captions no longer provoke even a chuckle. In the cartoon above, it is something about the seal that causes the drawing to still be funny. The caption can draw a smile, no more.

This is true of cartoons in general. As a lad reading the daily funnies I never saw the point of "Our Boarding House" or "They'll Do It Every Time." My father loved "Pogo" when he was young, and I can appreciate it mostly through his eyes. He later liked "B.C." which I could appreciate more. You usually have to grow up with characters to appreciate them, and they reflect their times. My granddaughters are mildly interested in "Peanuts," but the children in them are not part of their mental furniture.

Regarding old cartoons and comic strips, I am reminded of an anthology of old cartoons/joke pictures/comic strips that my parents had. It included Katzenjammer Kids, for example. Also Alfonse and Gaston- after you Alfonse. No, after you, Gaston.I lost track of the book. Maybe my brother has it. It was circa 1900-1920.

ReplyDeleteOne of the cartoons stuck with me. It showed a woman standing over a stove, kvetching to her husband: "You get to work in a nice cool sewer, and here I have to work over a hot stove all day."

In later years, that cartoon reminded me that while women back then didn't have it as good as women today, neither did the men. Which is something that latter-day feminists ignore completely.

Several years ago, I inherited a Thurber book, but I haven't delved into it yet.

RJ, I don't recall the name of that cartoonist, but I'm pretty sure I've seen his work, though maybe not that one in particular. Might have, though.

ReplyDeleteAvi, I remember reading Our Boarding House and They'll Do It Every Time (Hat Tip to Jimmy Hatlo). Pogo never really got me interested. BC did, somewhat. My mother, who died at 94, loved Zits; I was quite surprised when she told me that.

I still like Pogo: my avatar on some sites is Howland Owl.

ReplyDeleteBut as you remarked some time back, a lot of the humor is in the surprise in the social context, and when the context changes, or if the surprise _isn't_ anymore, the humor can dry up.

I wonder sometimes if humor isn't something like those surprise-centered berries Ransom found on Perelandra--best when you aren't spending time looking for it.

If you enjoyed B.C., good news: a movie is in development! I only discovered this because this month, 61 years after its creation and 12 years after the death of its creator, B.C. finally gave its female characters names. They are no longer "Cute Chick" and "Fat Broad," but now Jane and Grace. It's remarkable how long something nationally published can have something obviously problematic in it when it's been around for a while and no one really cares anymore.

ReplyDeleteAs a lifelong Thurber fan, I'll come to bat for his body of work: humor is both subjective and timely, and it's a rare feat to be able to last past the day and age that you produced your work in. Old New Yorker cartoons are rarely deeply funny to the modern eye, but reading a collection will provide sense of obscure pleasure and sometimes a wry chuckle. The individual elements don't hit the way they once did, but when you entrench yourself in the humor of a different era, your brain begins to shift gears, and you find yourself in rhythm with the patter of the era. It's the same way that a block of Shakespearean text seems utterly foreign and completely humorless at first, but its intentions becomes crystal clear and its jokes start to elicit real laughter when performed by capable actors. The problem is not the text, the problem is us.

Still, it's rare to create something that creates hearty laughter a century later. America's premier humorist is Mark Twain, and while we all recognize a lot of Twain's ideas as funny, his books don't tend to illicit continuous or even sporadic laughter. We love good old Tom Sawyer and his whitewashed fence, but you can read most of Twain's books cover-to-cover without laughing, and some have aged pretty badly.

So, while Thurber's collections of nagging wives and silly cocktail parties seem like relics from a different age now, it's remarkable that you can read any of it to an 11-year old and get genuine laughter. How many writers can you say that about a century or more later? Do you have anyone else on your list besides Thurber and Wodehouse?