In our Bible-study discussion of Islam, I noted that all the discussions by Muslims of their faith, and all written material that was quoted, made reference only to men. Given that the status of women in Muslim cultures varies widely between nations and classes within nations, I wondered what status the Koran gives women in theory. Are they spiritual co-equals, or is their status subsumed under their husband’s/father’s/tribal leader’s? Are they eligible for the same places in heaven, or are they lower in the hierarchy even there?

The disparity between theory and practice is enormous, as evidenced by these sites, on which Muslims comment to each other about Qur'anic teaching. The reports on the status of women are glowing, noting that the Qur'an specifically gives women the right to challenge even The Prophet, the right to vote, an entitlement to three-fourths of their children’s affection, economic and educational entitlements, and on through a long list. The contention is that Muslim women actually have more rights than modern women, without having to give up any of the privileges of protection and security that modern (read Western and western-influenced) have sacrificed.

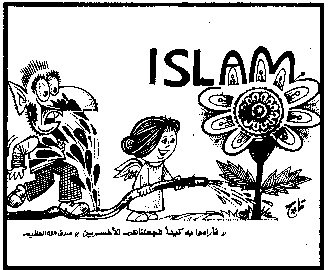

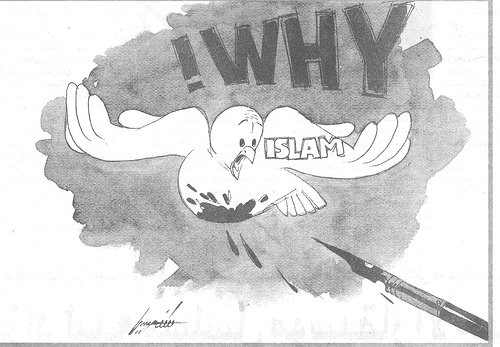

The recent cartoons from Egyptian newspapers (HT: Dr. Sanity) highlights this pretending that the ideal is the real. The innocent and harmless Islamic dove, the flower being watered by the cute little angel – are these really the images that Muslims have of themselves? Political cartoons exagerrate to make a point, but these images betray a deep unreality of perception. gcotharn over at neo-neocon relates an incident from his childhood, when the old men stood around and related how the South has come this close to winning the war but were betrayed by General Lee – a type of rewriting of history common to most cultures. All peoples want to showcase their ideals in purest form – there is certainly no shortage of pictures of Jesus blessing the children. But in these Islamic cartoons, the context is clearly about how Islam as an institution is treated in the world, not a picture of how wonderful Mohammed is. There’s a huge gap here.

Fouad Ajami wrote The Dream Palace of the Arabs, which deals with this vision and aspiration in the Middle East contrasting with its reality. Ajami’s focus is on the loss of pan-Arab high culture, but he doesn’t shy away from the larger discontinuity of Arabs in their thought processes. There is a constant invocation of long-past historical and mythological figures, Nebuchadnezzar, Osiris, Xerxes, called upon to be their representatives to the world. Even the first Gulf War was referred to by poets as “Rambo vs. Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon,” bespeaking an outrage that a debased and upstart society (us) should even approach the Cradle of Civilization. The past glories of their people are regarded as their True Self, and those who oppose them are seen as the opponents of all culture and justice. Islam intensified an unhealthy tendency already present – a tribal and national pride swollen beyond all legitimacy and reason.

All cultures and religions have this tendency to divorce the ideal from the real. Because Buddhism teaches that violence must be used only in self-defense, Buddhists regard themselves as a peaceful people, despite the centuries of unconscionable slaughter in their lands. Buddhism is in fact a way of adjusting to horror and evil, rather than changing them. Communism drew its power from the shell game of holding out the picture of the Workers Paradise which is just over the horizon, comrade, and in fact is already here, and always has been since we took power. Humanists have a vision of how life could be which doesn’t look at all like the French or Russian Revolutions, and can thus deny they had anything to do with those horrors.

This duality is not unknown in Christianity, of course. The attachment to how things are supposed to be, glossing over how they are, is a powerful human temptation. Much has been made of the medieval idealization of saints and the duality of images of women. Certainly there is a strong strain in Christian devotional literature of clinging to the Beatific Vision despite all earthly appearances – “It Is Well With My Soul” suggests the denial of reality. But here’s the thing. It stops well short of that verge. Suffering is not ignored but transcended. Evil is not denied or explained away but is overcome. I cannot, come to think of it, come up with a solid example of Christian literature where the ideal is held to be the only reality. The concept hovers at the edge of Christian ecstatic vision and experience, but does not overwhelm them.

There have always been voices in the church raised in protest that the ideal has not been achieved, measuring the promises against the reality. In Islam, the opposite seems to be occurring: the more ridiculously distant Muslim culture gets from its highest ideals, the more it is insisted that the ideals are embodied in current culture.

No comments:

Post a Comment